Depth charge

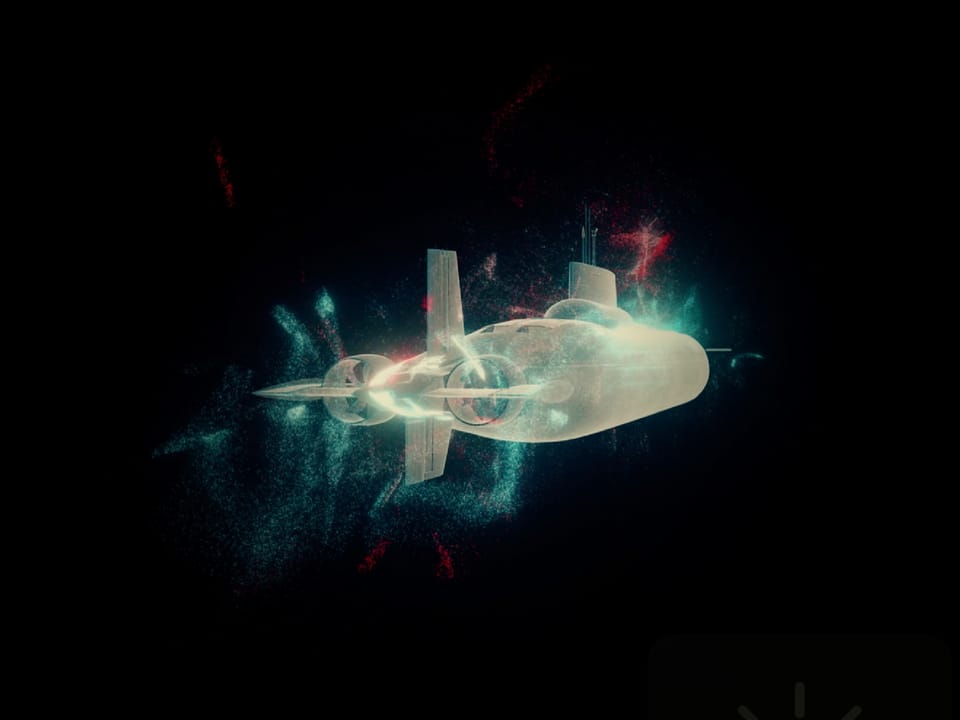

In a landmark defense deal announced on September 15, the United States is going to supply Australia with eight nuclear-powered submarines. Washington had previously shared its nuclear-submarine technology only with the United Kingdom, which co-founded the three-way alliance with the U.S. and Australia—known as AUKUS—presented by the three countries’ leaders in a virtual address. The security partnership also includes cooperation in cybersecurity, artificial intelligence, and quantum computing.

But the pact has provoked outrage in France, as Australia withdrew from a contract to purchase 12 diesel-powered subs from Paris, and French officials first heard about the breakup through media reports. France recalled its ambassadors to Washington and Canberra, the first time France had withdrawn its U.S. ambassador since 1778, when the countries established diplomatic relations—in a deal negotiated by Benjamin Franklin. The spat complicates U.S. President Joe Biden’s repeated pledges to repair alliances frayed by the Trump presidency, even as Biden strengthens ties with two other longtime allies. So why upset such a close partner now?

Jonathan Tepperman is the author of The Fix: How Countries Use Crises to Solve the World’s Worst Problems and the former editor in chief of Foreign Policy. Tepperman says the answer is China. The strategic goal of the coalition is to thwart China’s efforts to control the seas of the Indo-Pacific region, Tepperman says. In his view, Australia had long worked to maintain friendly relations with Beijing, but the new treaty reveals that Australia has chosen to openly side with the United States in confronting it. As Tepperman sees it, the People’s Republic has become increasingly belligerent under President Xi Jinping, and Australia’s move is only the latest sign of China’s deteriorating relations with neighboring and nearby countries …

Michael Bluhm: What’s the significance of the AUKUS deal?

Jonathan Tepperman: It’s important as much for the symbolism as the substance. It represents a major sign that another country, which has been trying to balance its friendship with the United States and its relationship with China, has decided that the balancing act is impossible. It is going to cast its lot with the United States, even at the risk of profoundly alienating China.