Living in a wartime economy

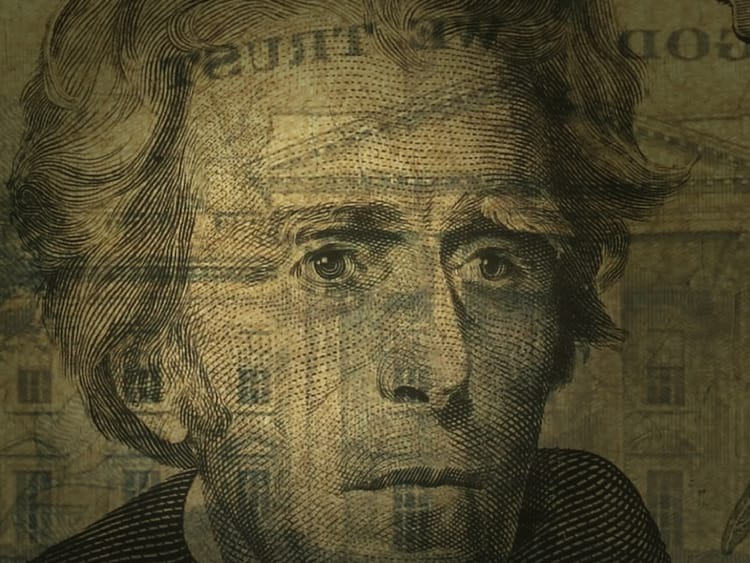

The wealthiest countries in the world moved, at the recent G7 summit in Hiroshima, to impose new sanctions on Russia. Their original sanctions, leveled immediately after Russia invaded Ukraine last year, included freezing state assets abroad, cutting off Moscow from the international payment system, and seizing the foreign property of Vladimir Putin’s associates and Russia’s oligarchs.

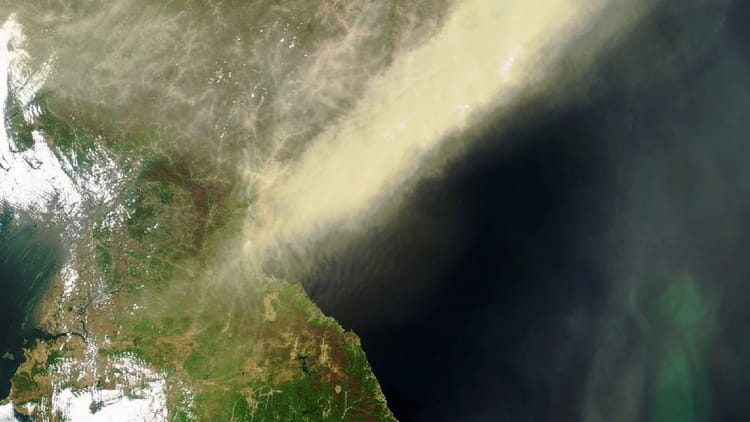

But the new sanctions show resiliency in the Russian economy since: Moscow has managed to evade them by importing goods through neighboring countries and allies, and also by using deceptive shipping technology to sell oil at prices higher than the limit set by the West. The International Monetary Fund is meanwhile predicting a slight rise in Russia’s GDP this year, and its inflation rate is 2.3 percent—lower than almost every Western country’s. Still, it’s tough to get a clear picture of the Russian economy, because Moscow is making increasingly more data classified, and Russian banks have stopped publishing a lot of financial information. So how do things really stand?

Sergei Guriev is the provost of the Paris Institute of Political Studies (Sciences Po), the former chief economist at the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD), and the former rector of the New Economic School in Moscow. As Guriev sees it, Russia’s economy is battered but not broken. The country is much more isolated than it was before the war in Ukraine, yet it’s still trading with China and other countries. In local stores, people can’t get top-quality Western goods anymore, but the shelves aren’t empty. Still, Guriev says, the sanctions are causing a meaningful shortfall in government revenues. So it’s unclear how Putin will end up balancing spending between the war and priorities at home, and how popular feelings will end up responding—to the war, and to Putin himself …

Michael Bluhm: Many economists saw the sanctions imposed after the invasion as unprecedented and tough, but it’s clear Moscow has been able to dodge some of them. What effect are they having on the Russian economy?

Sergei Guriev: Suppose, in a parallel universe, Putin invaded Ukraine in February 2022, and the West said, We’re busy with other things, so we’ll do the same thing we did in 2008 when Russia invaded Georgia: We won’t level any sanctions. If that’d happened, Putin would have had hundreds of billions of dollars in Russia’s sovereign wealth fund. He’d have no constraints on buying important military equipment. He could import American, French, or German equipment and produce more guns and rockets with the cash in the sovereign wealth fund. The war would have turned out very differently.