‘An existential question’

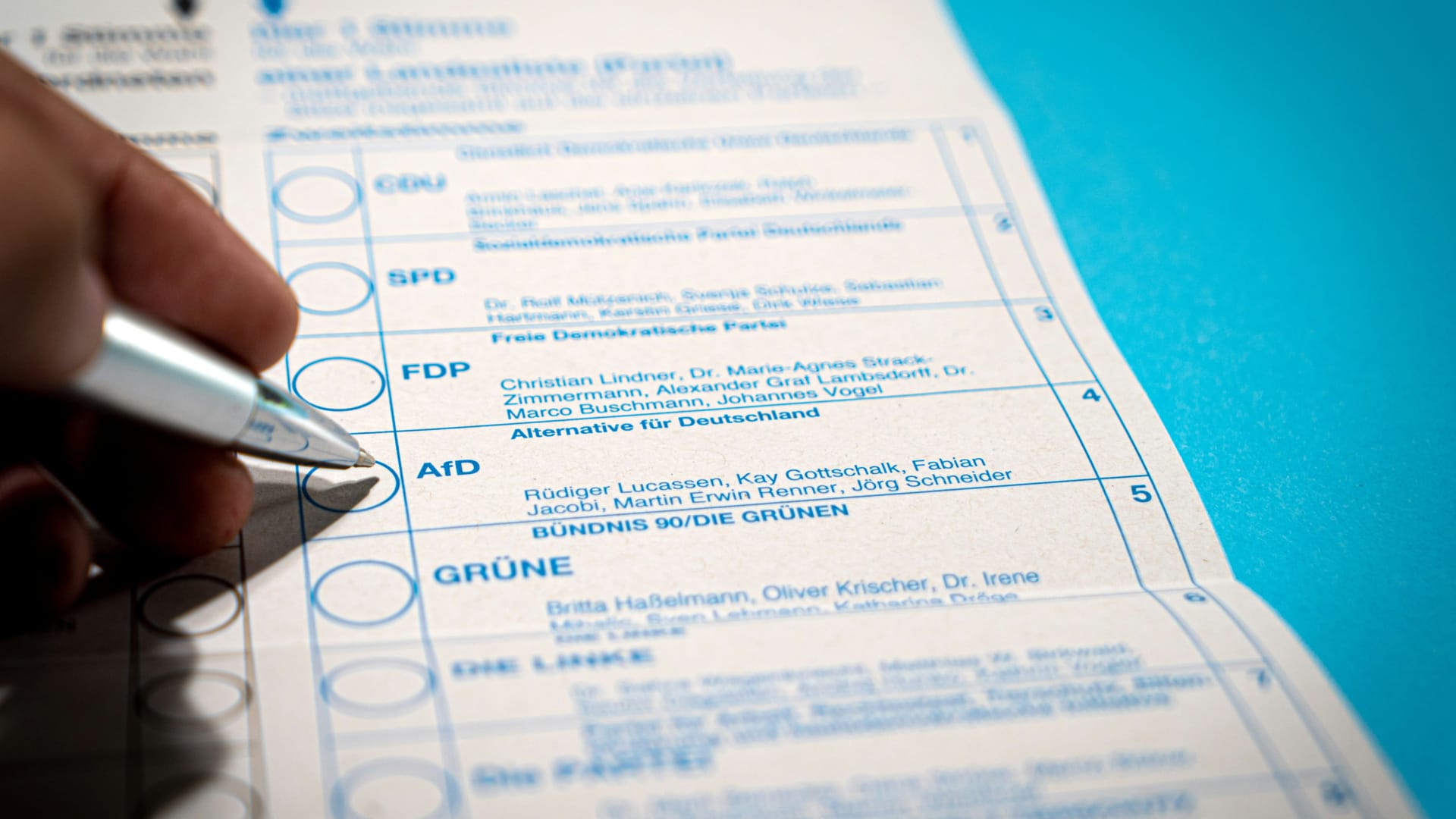

This summer, Europe’s far right made its greatest gains ever—at the ballot box. In the European Parliament elections, right-wing, nationalist parties advanced more than any others, winning dozens of new seats in Brussels. In France, National Rally nearly won control over the National Assembly, taking 53 more seats than in 2022. And in the U.K.’s general elections, the Reform Party won 14 percent of the vote, up from 2 percent in 2019. In the Netherlands, the Party of Freedom was finally able to form a government in July, after winning elections last November.

The new strength of these parties could mean dramatic policy changes, particularly in the areas of immigration and the climate—both at the EU level and within individual member countries. Or it could mean more than that: The far-right parties that came to power in Hungary and Poland have established a record of sabotaging democratic institutions by manipulating electoral laws, undermining judicial independence, and stifling independent media.

Still, despite their strong showings, none of these groups have managed to finish first in any European elections this year. And in the Netherlands, the longtime populist-right leader Geert Wilders could only forge a governing coalition in exchange for staying out of the cabinet himself.

So what does the far right’s new political standing mean for Europe?

Matthias Matthijs is a senior fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations and a professor of international political economy at the Johns Hopkins University’s School of Advanced International Studies. Matthijs says the far right’s recent successes in Europe obviously demonstrate broad support for its policy agendas—cutting immigration, slowing the reduction of carbon emissions, questioning EU funding for Ukraine’s defense, and so on. They also show a notable shift among these parties from a strategy of skepticism with Brussels to one of pursuing change from inside the EU’s institutions. But perhaps more importantly than anything, Matthijs says, the far right’s new political standing in Europe shows how mainstream its ideas have become—especially on immigration. Across the continent, more and more people are seeing the issue as a question of survival for their countries, their communities, and their lives—very much as the nationalists have been insisting.

The complication is, too few of Europe’s political leaders—on the left or the right--are willing to be candid with their voters about just how much they need immigrants in the first place …

Michael Bluhm: What’s happening here?