‘It’s a hydra’

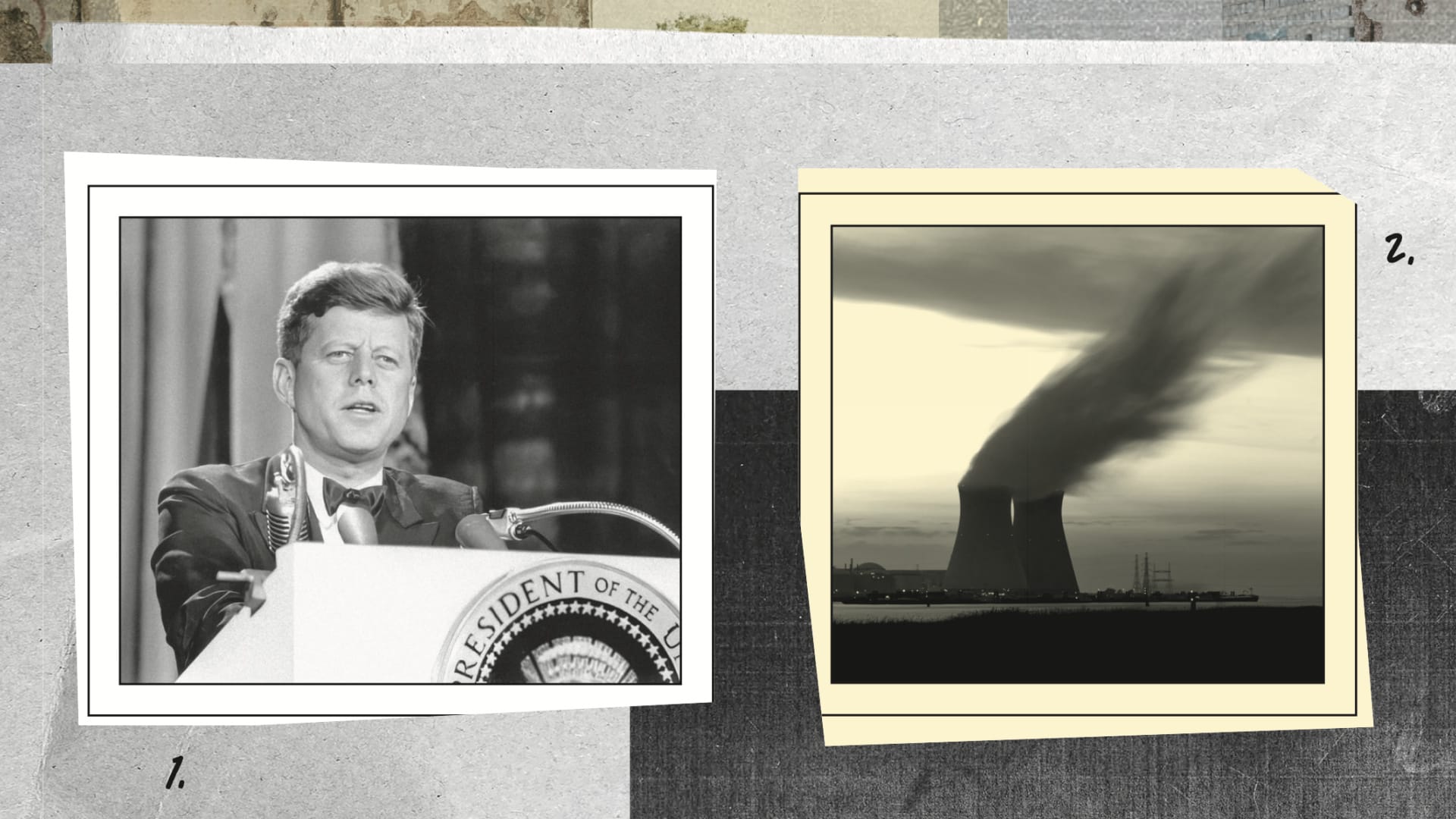

After the assassination of U.S. President John F. Kennedy in 1963, the Soviet Union actively spread disinformation about the murder—partly because the Soviets feared they might be blamed for it, partly to exploit shock and confusion, sow discord, and undermine faith in American institutions. The central narrative they pushed may be familiar: Kennedy was killed not by Lee Harvey Oswald alone but by a right-wing conspiracy of wealthy businessmen, military leaders, and intelligence officials who opposed Kennedy’s policies on Cuba and nuclear-arms control. Back then, an operation like this was labor-intensive—the KGB planted false stories in left-wing newspapers around the world, fabricated a letter tying Oswald to the CIA officer E. Howard Hunt, and so on—but it got a lot of traction, particularly in left-leaning European media. And the narrative has circulated ever since, among conspiracy theorists and in pop culture—including as the basis for Oliver Stone’s 1991 thriller JFK.

Throughout the Cold War, the Soviets conducted plenty more covert influence campaigns against the U.S. and other Western democracies. In the 1950s and ‘60s, they tried to exploit racial strife in America, even forging letters to civil-rights organizations purporting to be from the Ku Klux Klan. In the ‘70s and ‘80s, they tried to radicalize Western anti-nuclear movements through front organizations, funded research, and media manipulation. In the ‘80s, Operation Infektion promoted the false claim that HIV/AIDS was created as a biological weapon at Fort Detrick, Maryland. China had its own operations. Cuba, East Germany, and even North Korea had theirs.

In the meantime, the Soviets had become masters in the arts of strategic corruption and compromising material (kompromat). Often, they’d identify and cultivate relationships with influential Westerners who had financial troubles, proclivities for vice, or ideological sympathies the KGB could work with. They’d offer bribes, business deals, or other financial incentives through front companies and intermediaries to compromise their targets. They focused on corrupting politicians, journalists, and business leaders in positions to influence policy or public opinion. In Western Europe especially, they targeted politicians and labor leaders through both direct payments and lucrative business arrangements.

It’s still not clear how strategically effective many of these operations were. But they were often damaging, and they were ongoing.

Strategic corruption by autocracies toward democracies, in other words, isn’t new. Part of what is new is the players: When the Berlin Wall fell in 1989, Dubai was a small city in the desert. Now, the United Arab Emirates is the fourth-largest economy in the Middle East and a key U.S. ally. Part is the context: Since the 1990s, a hyper-globalized economy has transformed and connected autocratic and democratic societies; money tied to the Chinese Communist Party, the post-Soviet Kremlin, and, increasingly, the ruling families of the Gulf states has flowed into Western capitals; and digital technologies are now driving more than 729 million real-time financial transactions a day—not to say the virtually constant consumption of media and messaging. But no small part of what’s new are the stakes: Amid all these changes, democracies’ threat interface—the set of ways attackers can interact with or exploit a system—has become more complex and rapid-changing than ever. What can democracies do?

Josh Rudolph is a senior fellow and the head of the Transatlantic Democracy Working Group at the German Marshall Fund. Rudolph says that in the developing world, the challenges of responding are relentless, both because there are so many vulnerabilities to strategic corruption and because there’s so much opportunity for corrupt actors to interfere with investigations. But developed democracies, including the most powerful in the world, face their own relentless challenges. While some have made headway through legislative initiatives and enforcement, they all struggle to close legal loopholes faster than new ones open up. And in the United States, especially, this struggle has been complicated not only by the jarring priorities of a new administration, but also by a long-term trend among American legislators —to put partisan political advantage ahead of national security ...

From Altered States, a print extra created in partnership between The Signal x the Human Rights Foundation.

Allison Braden: Ben Freeman and Miranda Patrucić describe some of the most powerful autocracies in the world engaging in an array of influence activities—some legal, some not.

It seems the Persian Gulf states are the big players in more developed democracies like the U.S. or the U.K.; China and Russia, in less developed democracies. Some of these operations are focused on economic ends, some on geopolitical ends, some on defending autocracy itself. What patterns stand out to you?