Enigmas

When Hurricane Harvey hit Texas in August 2017, it triggered one of the most destructive natural disasters in American history. The storm stalled over Houston for several days, dumping an unprecedented amount of rain, more than a meter in some areas, leading to catastrophic flooding that put about a third of the city underwater. More than 100 people died. Around 30,000 were displaced from their homes. Some had to be rescued by boats and helicopters. Many needed temporary shelter. The storm overwhelmed local infrastructure and emergency-response systems, destroyed or damaged hundreds of thousands of homes, and ended up causing about $125 billion in damage.

One of the swiftest and most extensive humanitarian-relief efforts came from the United Arab Emirates. Coordinating through their embassy in Washington, D.C., and with the Emirates Red Crescent, the U.A.E. donated $10 million to Houston and surrounding areas, working with local organizations like the Greater Houston Community Foundation to help rebuild homes, schools, and community centers, and helping restore damaged medical facilities. “As Houston builds forward from the hurricane,” Mayor Sylvester Turner said, “we cherish our helpful partners such as the U.A.E.” Some communities in and around Houston are still dealing with the impact of the hurricane; many of them still remember the vital support.

Earlier the same year, three U.S. intelligence agencies—the Central Intelligence Agency, the Federal Bureau of Investigation, and the National Security Agency—released a declassified report detailing a coordinated Russian campaign to influence the 2016 presidential election. It included hacking into Democratic Party email systems and releasing stolen information through WikiLeaks, using social-media platforms to spread disinformation and divisive content, and targeting election systems in multiple states.

The Russian Internet Research Agency created fake social-media accounts and paid for political advertisements to spread propaganda and inflammatory content. An investigation by Special Counsel Robert Mueller, the former director of the FBI, led to multiple indictments of Russian intelligence officers, along with the former head of Donald Trump’s campaign, and detailed how Russian military intelligence carried out cyber operations targeting election infrastructure and political organizations.

While the scale and sophistication of this campaign were remarkable, its impact on the election outcome was never definitively measured, if that were even possible. Meanwhile, a number of prominent allegations about Russian interference in 2016 didn’t hold up to scrutiny. The most notable was the “Steele dossier,” a collection of reports by the former British intelligence officer Christopher Steele, published by BuzzFeed News, that included salacious claims about Trump’s ties to the Kremlin. Many key elements of the dossier remain unverified, and some have been proven false. McClatchy and other news organizations debunked the allegation that Trump’s lawyer Michael Cohen met with Russian officials in Prague. The Mueller investigation, the FBI, and the Department of Justice’s Office of the Inspector General all investigated claims about ongoing communications between Trump Organization servers and Russia’s Alfa Bank, and found them to lack merit. Initial media reports suggesting Russian agents hacked into Vermont’s power grid turned out to be wrong. The story that the Trump campaign actively conspired with Russia—which media coverage often referred to as “collusion”— was never substantiated, including by Mueller, whose team found insufficient evidence to establish any criminal conspiracy at all between the Trump campaign and Moscow.

It’s not always clear where foreign influence ends and interference begins—or even where benign foreign activity ends and influence begins: Houston may be a crucial energy-industry hub, important to the U.A.E.’s oil and gas interests; and the city’s aerospace industry, centered around NASA’s Johnson Space Center, may be increasingly important to the U.A.E.’s ambitions with its space programs; but neither makes the millions it put into disaster relief in Houston malign.

It’s also not always clear where the appearance of foreign interference is a specter—or even whether the reality of foreign interference has mattered much at all: Russia may have targeted U.S. elections in 2016 and 2020, as it would seem to have targeted Romanian, Moldovan, and Georgian elections in 2024; but it can be hard to say how far some of these disruption operations have gone or how much they’ve actually affected democratic outcomes. It can even be hard to distinguish dispassionate assessments of evidence of electoral interference from vexed narratives fueled by partisan grievances. Still, as Ben Freeman and Miranda Patrucić illustrate, any line of autocratic influence is a potential form of interference—and any form of autocratic interference is a potential vector of corruption. So what’s corruption here and what’s not?

Justin Callais is the editor at large for The Signal and the chief economist at the Archbridge Institute. While in some cases, the question is a matter of factual uncertainty, Callais says that in all cases, it’s a matter of interpretive ambiguity: When we understand something as corrupt, we don’t understand it simply as the violation of an enforceable rule; we understand it fundamentally as the degradation of a common good—and common goods can be debatable; they can be elusive; they can compete with one another; they can even change over time. Still, we can’t understand democratic life without understanding the common goods it’s grounded in—and, Callais says, we can’t understand autocratic systems without understanding how they depend essentially on degrading those common goods ...

From Altered States, a print extra created in partnership between The Signal x the Human Rights Foundation.

John Jamesen Gould: Do you know corruption when you see it?

Justin Callais: It can be tough, because corruption isn’t a legal concept. You sometimes hear that so-and-so was arrested on corruption charges, but people don’t really get arrested for corruption; they get arrested for wire fraud or something specifically criminal like that. Wire fraud is illegal. Corruption can happen on either side of the law. As an idea, it depends on the thing being corrupted, what the purpose of that thing is, and then what some intentional human behavior might be doing to undermine that purpose.

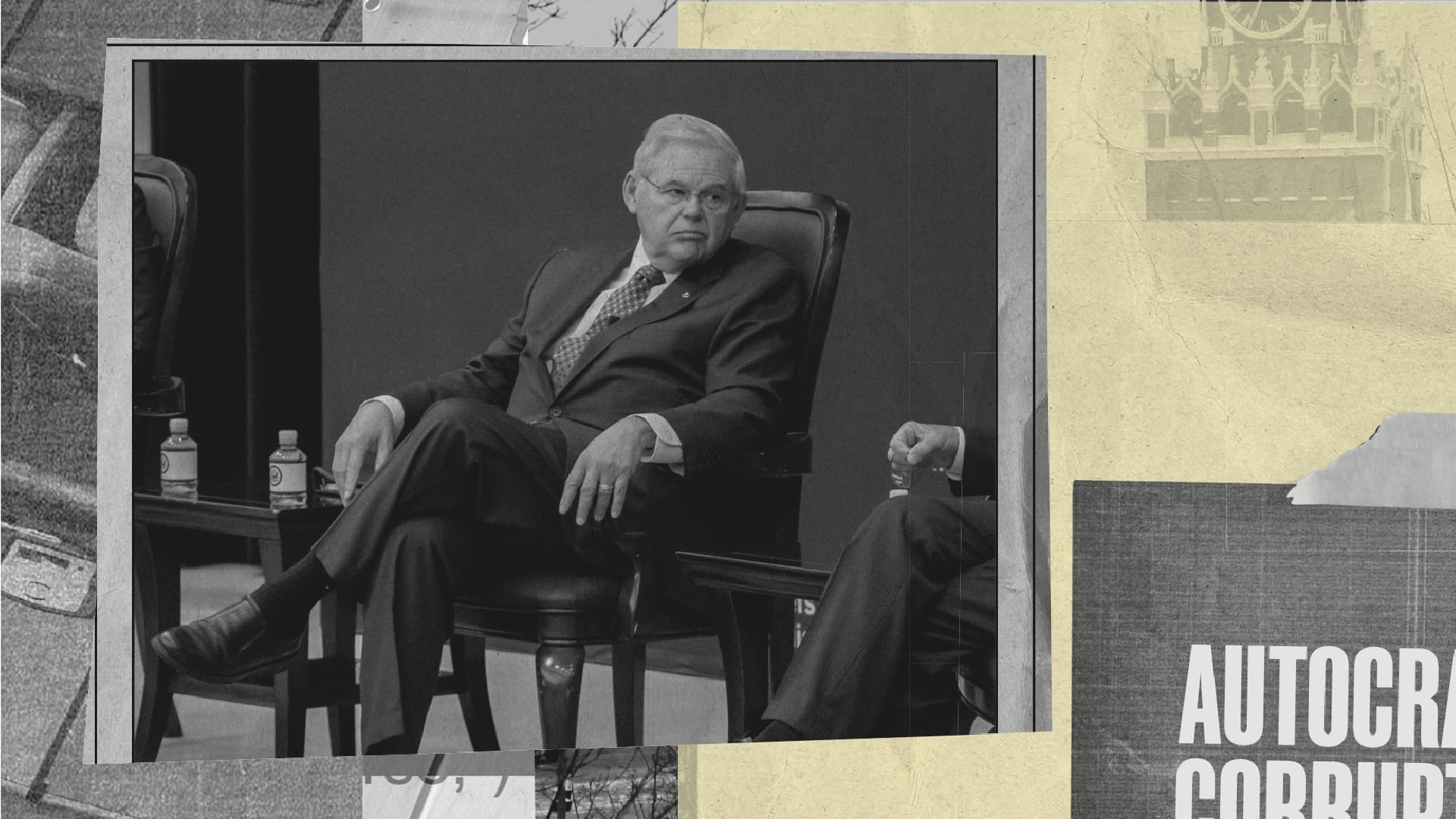

When people talk about corruption, we tend to mean the abuse of authority for personal gain or some other end that’s not in the common interest. In politics, that might mean someone taking bribes—like we’ve seen with Bob Menendez and some of these other recent cases in the U.S.—or where someone embezzles public money or appoints his kid to a public job, or manipulates regulations or contracts for her benefit. In business, it could mean insider trading or colluding to fix prices, or fraudulent accounting—things like that. In any case, it’s a betrayal of the interest someone’s meant to be serving.

So corruption isn’t just, or even principally, a matter of illegal acts. It can be a matter of legal but unscrupulous acts—even including when powerful interests actually go and shape laws and regulations to their advantage, through lobbying or otherwise. That’s part of how corruption can adapt and persist even within formally legitimate frameworks.

Gould: Corruption isn’t legal language; it’s moral language.

Callais: Moral language that makes different sense in different areas of human life—depending on the kinds of common good people understand themselves to be working toward together, what it means to uphold trust in working toward that common good, and so on.

Corruption isn’t just, or even principally, a matter of illegal acts. It can be a matter of legal but unscrupulous acts—even including when powerful interests actually go and shape laws and regulations to their advantage.

The word corruption comes from the Latin corruptio. To corrupt is corrumpere—literally, to destroy something. But in everyday life, corruption came to mean either physical degradation, like what happens when an illness starts breaking down someone’s body, or moral degradation, as when someone loses their integrity or virtue. Eventually, over the last couple of hundred years, the physical sense more or less fell away and the moral sense became the usual meaning.

Gould: You mention this language also applying to the ways powerful interests can shape the law itself to their own purposes—and that being part of how corruption adapts and persists. Which seems to raise the question of a corrupt system, because it raises the question of how powerful interests are able to hack the system to their ends in the first place. How do you understand the relationship between corruption at the individual or even group level and corruption at a systemic level?

Callais: You could look at it this way: Corruption is almost never just a matter of individual moral failings. It thrives specifically in systems with weak institutional oversight, low transparency, and bad accountability mechanisms. But more than that—and this is part of what makes corruption so challenging to address—it can become self- reinforcing. It can create negative-feedback loops, in which people feel compelled to participate in corrupt practices just to get by, or in which they may come to feel it’s all normal and embrace it. In those ways, it can become systemic, and systemic corruption is self-cultivating.

In the United States, I’m afraid there isn’t a better example of systemic corruption than my home state of Louisiana. Corruption is almost as ingrained in our culture as Mardi Gras or po-boy sandwiches. Get this: In 1991, Edwin Edwards, a convicted felon, was running for governor against David Duke, the grand wizard of the Ku Klux Klan—and Edwards supporters were using these incredible, unofficial campaign slogans: “Vote for the crook: It’s important.” Or: “Vote for the Lizard, not the Wizard.” These were on bumper stickers.

Still today, Louisiana consistently ranks as the most corrupt state in the U.S. And if you want to understand why, it’s not because we somehow keep having inherently corrupt people born here; it’s because in Louisiana, corruption became systemic—just a way of doing business.

Gould: How?

Callais: You can tie it back to the Napoleonic Code from the early nineteenth century. In 1800, a year after Napoleon took power in France, he bought Louisiana from Spain and put a legal system in place that arrogated enormous power to the governing executive. Unlike the English common law, which was designed to limit the power of the monarchy, Napoleon’s code was designed to preserve and enhance centralized power—ultimately, his power—insulating it from judges or other competing powers.

You can see the consequences of a system like that emerge with time. By 1873, state legislators were accepting stocks in the Crescent City Livestock Landing & Slaughterhouse Company, and officials in New Orleans were taking bribes, in return for supporting a law to give the company a monopoly there.

Corruption is almost never just a matter of individual moral failings. It thrives specifically in systems with weak institutional oversight, low transparency, and bad accountability mechanisms.

That’s an infamous example. The Louisiana State Lottery Company similarly handed out bribes to secure a monopoly at the state level, before the government turned around and banned lotteries altogether in 1893—after which the company incidentally moved to Honduras and kept issuing tickets into the U.S. illegally for another 22 years. They were determined.

In all events, a corrupt system creates a powerful chain of cause and effect. It isn’t just a bunch of individuals being corrupt together. It isn’t just “culture,” either, although that’s closer to the mark. It’s a whole system—of laws and norms and established practices together. It may be built intentionally from the top down, or it may be built sideways by people who find vulnerabilities in an existing system. But where corruption becomes systemic, it trains people inside the system, and it draws in new people who find themselves suited to it. It naturally reinforces itself.

Gould: How does that matter? Corruption, in the modern sense, is a moral concept; systemic corruption, in the way you describe it, is clearly bad news as a moral phenomenon. But how far do the effects of corruption go? What would you say about that in general terms?

Callais: The effects go very far. We could ask a lot of different people with different kinds of specialized knowledge about it and, I think, learn more than we might imagine about the effects of corruption in all different areas of life—on people’s everyday experiences, on their culture, on political outcomes, and so on. But as an economist, I can tell you, there are significant economic costs.

And the costs of systemic corruption are especially severe. Systemic corruption distorts markets. It misallocates resources. It discourages legitimate business investment, as people face unpredictable costs from bribes and unfair competition. Government revenues decline on account of tax evasion or the theft of public funds, reducing the quality of infrastructure and public services. This all creates a vicious-cycle dynamic where poor services and weak institutions lead from systemic corruption to worse systemic corruption. The economy becomes less efficient as contracts and opportunities go to people with political connections rather than the most qualified. All of which ultimately leads to lower productivity, reduced innovation, slower growth, and widening inequality as wealth concentrates and circulates among corrupt elites.

You can see that in how Miranda Patrucić talks about China using corruption in the developing world in ways that benefit corrupt elites at the expense of their countries’ economies, just as you can see it in the GDP of Louisiana over time.

But again, that’s just an economic answer to the question. The effects it describes are extremely consequential and yet still partial. In politics, for example, the idea of foreign elements overriding the power of citizens may be fraught and complicated—the stuff of xenophobia or paranoid conspiracy theories—but on any operative understanding of democracy in the world today, a question about that kind of influence is a question about corruption. That’s built into the idea of democracy.

The costs of systemic corruption are especially severe. All of which ultimately leads to lower productivity, reduced innovation, slower growth, and widening inequality as wealth concentrates and circulates among corrupt elites.

Gould: Autocracies have their own operative understandings of foreign interference as corruption. The governments of China and Russia both regularly talk about U.S. and Western influence this way. The government in North Korea goes on about it all the time. Running-dog lackeys and so on ...

Callais: They do. It gets at the irony in the names of the People’s Republic of China or the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea and the like—all autocracies, claiming exclusive authority on behalf of the people they rule over. So they say anyone who’s against their governments, or virtually anything their governments do, is definitionally corrupting the only legitimate system.

Still, when it comes to any form of corruption we’d understand as undermining a democratic society, we can always find versions of it within that democratic society—but it’s also always more likely to be entrenched at scale in an autocratic society.

It’s striking. If we look at the most and least corrupt countries, according to Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index, four of the top five countries are full democracies, scoring highly on indicators of democracy in the Economist Intelligence Unit’s Democracy Index: Denmark, Finland, New Zealand, and Norway. Singapore is the only country in the top five that doesn’t score highly on those indicators, though it does score above average. And TI’s bottom five, the most corrupt countries, are autocratic basket cases like Somalia, Venezuela, Syria— under the recently departed Bashar al-Assad— South Sudan, and Yemen.

There’s some variation in the correlations TI finds between its corruption indicators and democracy indicators overall, but none of it obscures the fundamental relationship between corruption and autocracy—which is structural: Autocracies are structurally corrupt; they build systemic corruption into the structure of the state.

Autocracies aren’t all full-on kleptocracies, the purest form of structural corruption—states whose leaders use their power to steal wealth and use their wealth to maintain power. Or at least, they’re not all equally kleptocracies. But the structural corruption of autocracies naturally bends them toward kleptocracy.

Gould: “Power tends to corrupt, and absolute power corrupts absolutely.”

Callais: That’s as true now as it was when Lord Acton wrote it in 1887. Which is why, when Miranda Patrucić talks about the Kremlin fearing democracy as a threat to its own autocratic system, she’s not only right; the Kremlin is right. However imperfect any democracies are, they essentially depend on and cultivate ideas and institutions that distribute information, wealth, economic power, and political power. Those ideas and institutions are threats to autocracies. They’re existential threats to kleptocratic autocracies. And we know they know this, because the evidence of kleptocratic autocracies trying to disrupt democratic life is overwhelming, even if sometimes it’s ambiguous or its effects are uncertain.

It’s also why democracies have to—I won’t say fear autocracy as a threat to their system, but be clear-eyed about it. As Ben Freeman says, you take it with you: Structural corruption inevitably brings strategic corruption. And if you’re a dictator, and you can use strategic corruption where relations are friendly and commerce with you is legal, great—because now you’re using strategic corruption to bring influential democratic citizens into the kind of structural corruption your power depends on.